COP 22- Knowledge and Learning: Strategies for Managing Climate Change

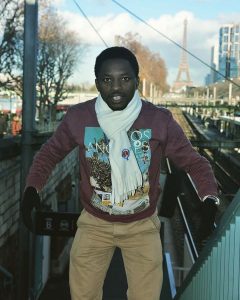

By Olumide Idowu

Education: the key

Many Africans are aware that some changes occur in the environment year in and year out but they need to understand such change: increased disease, food shortages, and extreme flooding at various localities during certain periods of the year. Yet there have been no efforts to reduce the occurrences or avert them altogether. It is urgent to educate the public of the signs of climate change as well as management and prevention strategies.

Many of us are aware that climate change is severely affecting livelihoods in Africa through changes in rainfall patterns. About seventy percent of the farmers expressed that their crops were washed away by floods, eliminating their yields for consumption or sale. In some part of West African countries the fishermen were not spared since they could not catch as much fish as they used to and the environment was not conducive for human life since all the debris washed away by water or flood was deposited at various places. About 70 percent of them at various fishing ports lamented that they suffer this disaster yearly but do not have the solution to their problems. According to Zack [1], Knowledge Management consists of a series of strategies and practice used in an organization to identify, create, distribute and enable adoption of insights and experiences. Such insights and experiences consist of knowledge integrated into or embodied in organizational theories and practice [2].

For many years, researchers have explored local knowledge about environmental change and increasingly over the past decade, local knowledge in relation to climate change specifically. They know much more about the content of the different types of knowledge that are important for responding to climate change-from modeling future rainfall changes in a particular country to how to get the most out of an agricultural environment in highly variable conditions. However, they still do not know how to translate these different forms of knowledge into practice and make them accessible to policymakers, front-line staff (such as agricultural extension officers or health workers), and people in poor communities on the ground. They also have a poor grasp of strategies for bringing together people from different backgrounds and starting points, so that they can reconcile what they know. Bringing together different perspectives is important for both the quality and legitimacy of decisions about adaptation [3].

In African schools, practical demonstrations are needed in order for children to actively use their acquired knowledge and skills to improve society. Teachers should also demonstrate the importance of agriculture in the growth of the nation. In the fishing ports where fish farmers and their children reside, experts should be sent to demonstrate the modern way of processing and preserving fish both for local consumption and for exportation. Children should be thoroughly guided so as to enable them do the same in their various localities.

There is a need to strengthen climate change knowledge architecture in Africa to reach policy-makers, students and researchers, as well as community-based organizations and NGOs, who are in the frontline of delivering adaptation projects. This knowledge architecture has already been developed in Nepal (Nepal Climate Change Knowledge Management Centre). Ideally, it would include a center that would serve as a platform for coordinating and facilitating the regular generation, management, exchange and dissemination of climate-related knowledge and capacity-building services. Climate change researchers who receive grants through the project would be provided with mentoring in learning and knowledge sharing. The Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) has contracted an external consultant to drive the monitoring and evaluation of the project, whose role is to ensure that learning from the project, is captured and used throughout the project’s implementation [4].

It would be instructive for the African governments to borrow a leaf from Nepal to drive climate change knowledge at home for the benefit of the citizenry. It would benefit the agriculturists who make food available to the people, the students who would gather knowledge to disseminate to people in our various communities, and the policymakers and managers of education who would ensure that such knowledge is part of the education curricula. It might attract investors to the country, thereby creating job opportunities.

How can it work ?

The World Bank is noted for its development project lending; knowledge services are becoming increasingly important. Governments, private sector and civil society organizations are eager to learn from others what is working and what is not working when it comes to climate change. Knowledge exchange, South-South learning, communities of practice and training are crucial to ensure that development gains can be sustained and lead to lasting results. The new Climate Change Knowledge Portal, the Open Data Initiative, Mapping for Results, the Green Growth Knowledge Platform and Connect 4 Climate Change are a few examples of how the World Bank shares knowledge and connects practitioners around climate change [5].

Knowledge is strategically important in technology, teaching and learning. In order to survive and thrive, institutions of learning, primary, secondary and tertiary, must ultimately engender a knowledge culture, grappling with information and knowledge management, and developing accessible technological systems along with the associated tools and resources.

What African children need is practical application of the theories of climate change that they have learned. Students should be taught to put their knowledge to meaningful use, which is only possible when educators practice what they teach so as to guide the learner properly. African schools should be well equipped and teachers should receive further training to update their knowledge and skills. The present curricula will not enable Africa to compete with other developed economies. As agents of change, children can assist in educating their communities in their various localities to adapt to climate change. When African children are provided with adequate knowledge and skills, coupled with sufficient infrastructure, there will be less damage sustained from climate change.

A United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) report [6] showed that the level of awareness about climate change is rather low in Africa and, if care is not taken, will wreak havoc on the daily lives of its citizens. The report showed that the awareness of climate change is highest at the federal level but drops at the state and local government levels where knowledge is highly needed. These levels encompass the people who own and cultivate farmland. As Olorunfemi [7] asserts, the most significant obstacle to reducing the impact of climate change in “Nigeria” is lack of awareness and knowledge. For this reason, knowledge management must be taken seriously. In addition to educating the citizenry through Town Criers and village gatherings, the government needs to incorporate climate change into the school curriculum in order that school children, the agents of change, can gain new knowledge and skills. Considering the youthful exuberance, inquisitiveness, enthusiasm in these children, the information passed on to them should be looked upon as knowledge delivered. Coupled with the latest technology with which many of them are conversant, the information could be easily delivered and the impact felt within a short time within the school system [8].

In Conclusion, education system should be proactive and effective so as to make the learners (primary, secondary, and postsecondary students) conveyors of information who can effectively address the issue of climate change. In short, climate change education should be considered with all seriousness and given the attention it deserves in our educational system.

Thank you

Olumide Idowu is the Co-Founder, Climate Wednesday. He can be contacted on Twitter via @OlumideIDOWU

Reference:

- Zack, M. H. (1999). Managing codified knowledge. Sloan Management Review, 40(4), 45-58.

- Anuna, M. C., Amanchukwu, R. N., Edem, E., & Nzewunwa, O. P. (2013). Knowledge and learning management (KALM): Potential challenges to leadership in education. Africana Studies Review, 3(3), 91-102.

- Newsham, A. (n.d). Climate change, knowledge and learning Retrieved June 30, 2014 from https://www.ids.ac.uk/idsresearch/climate-change-knowledge-and-learning.

- CDKN (2012). Strengthening climate change knowledge architecture in Nepal. Retrieved May 2014 from http://cdkn.org/project/strengthening-climate-change-knowledge-architecture-in-nepal/?loclang=en_gb.

- World Bank (2011). World Bank Institute global dialogue series on climate change: The road to Durban. Retrieved March 20, 2014 from http://wbi.worldbank.org/wbi/stories/world-bank-institute-global-dialogues-climate-change-%E2%80%9C-road-durban%E2%80%9D.

- UNDP Project Report (2010). Climate change awareness and adaptation in the Obudu Plateau, Cross River State. Retrieved May 29, 2015 from http://aradin.org/modules/AMS/article.php?storyid=11.

- Olorunfemi, F. (2010). Risk communication in climate change and adaptation: Policy issues and challenges for Nigeria. Retrieved June 30, 2014 from http://iopscience.iop…org/1755-1315/6/41/412036/pdf/ees9 6 412036.pdf.

- Amanchukwu, R. N., & Ezekiel-Hart, J. (2013). Youth conflict challenges and management for self-actualization in a developing nation. International Journal of Educational Foundations and Management, 1(2), 78-96.